As I walk through the narrow aisles lined with wooden vegetable stands, arms aching from the black plastic bags loaded with tomatoes, cabbages, bananas, and onions, I hear my name called from behind me. “Heidi!” I turn to see the smiling face of Hassan, the young Ugandan man that I regularly purchase dania (cilantro) from each week. He walks over, handing me a large watermelon, and says “a gift for you.” It’s moments like this that make Soroti feel like home.

Soroti is the main commercial and administrative center of Soroti District in the Eastern Region of Uganda. The actual town is relatively small compared to my previous stay in Kitale, Kenya. Many of the buildings only reach as high as two stories and there are no major supermarkets. Yet, what Soroti lacks in size, it makes up for in history.

The aging buildings around town give a glimpse into Soroti’s rich historical past. Soroti previously had a large Indian population, which was dispelled from Uganda during the dictatorship of Idi Amin in the 1970s, and whose presence is reflected in the surrounding architecture. In addition, Soroti is known for the picturesque Hindu temples, Muslim mosques, and Sikh gurdwaras that are built beside local butcheries, clothing shops, and restaurants.

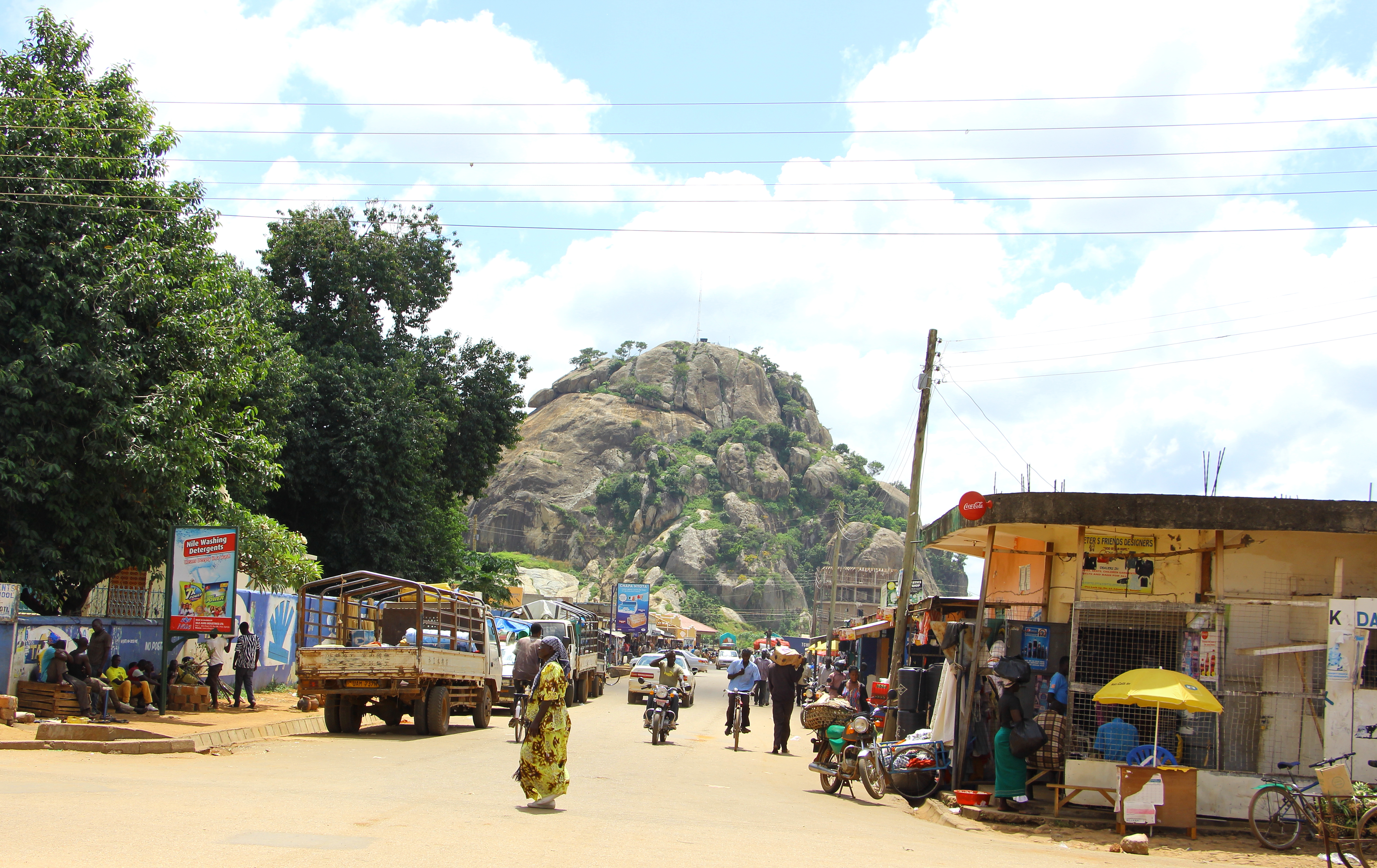

It’s hard to get lost in Soroti. No matter where you stand in town, a large rock formation known as Soroti Rock stretches into the sky, making it a handy navigation tool. I recently learned that this rock is a volcanic plug, formed when magma hardens within a vent on an active volcano. It is technically illegal to climb Soroti Rock both because of its clear view of a military training facility and because it houses water tanks that supply the entire district. But a fun fact: there is a welcoming security official that lives on the top who you can bribe with 10,000 shillings ($3.00) to experience the spectacular view.

Despite its small size, Soroti is bustling during the day. Lines of bikes and motorcycles speed through town, making it difficult to cross at intersections. Stalls line the streets selling sizzling machomo (roasted meat), mouth-watering rolex (fried eggs rolled in chapati), and scratchable phone credit cards. When walking down the main street, it is hard to miss the rows of tailors and seamstresses stepping on foot petals, sewing school uniforms or creating a new dress out of boldly patterned cloth.

Our office is located right outside of town, a short 15-minute walk that sometimes can feel like eternity, thanks to the searing Soroti sun. While Soroti is much warmer and drier than our office in Kenya, the El Niño rains have left the roads thick with mud and have kept the grasses surrounding our office green. I have joked with coworkers that we should start a farm because our office backyard is home to jackfruit, orange, mango, avocado, and apple trees.

The villages we operate in are a significant distance from our office. For example, Field Coordinator Gerald Kyalisiima works with business owners around the city of Lira. It takes over two hours on matatus (public buses) to reach the city of Lira. The journey doesn’t stop there. In order to reach the rural villages we work in, Gerald must take a boda-boda (motorcycle) that takes at least another hour on bumpy dirt roads. These areas are also prone to severe storms and major flooding, meaning that at times the roads leading to these villages are impassable.

There is a reason that we work in the rural areas surrounding Soroti. This part of Uganda was significantly affected by The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a violent rebel group that was led by Joseph Kony and has been accused of widespread human rights violations. Many of the people in these villages lived in daily fear and were forced to flee to internally displaced camps. In fact the UN’s refugee agency, the UNHCR, claims that more than 1.8 million internally displaced people were moved into 251 camps. Following the peace agreements in 2007, many of these people moved back home or resettled in new areas. Despite the end of the violence, extreme poverty remained prevalent. It is the goal of Village Enterprise to provide our business owners in these regions with the training and start-up capital to create sustainable business, to empower them to create a better life for themselves and their families, and to help restore peace and stability to these communities.

During disbursements in Oseera, one of our business owners performed a moving skit: “My name is Poverty. I do not move alone. I move with my brother, Famine. Where you find one, you will find the other. We can be eliminated in the society. Which society? The society which is ready to change like the society of Oseera which has joined with Village Enterprise. I, Poverty, and my brother, Famine, we are ready to change because the society of Oseera has acquired knowledge from Village Enterprise.” There are no words to describe the power of resilience witnessed in these villages and our business owners’ eagerness to create change within their communities.

A view of Soroti Rock from a main street in town.

A view of Soroti Rock from a main street in town.